-

Zach Zono, Two Front Doors, One Exit

Zach Zono, Two Front Doors, One ExitThe Gravity of a Dream

Nico Kos EarleOpening: Saturday 17 January, 2pm

FRED LEVINE, The Old Silk Barn, Quaperlake Street, Bruton, BA10 0HB, UK

-

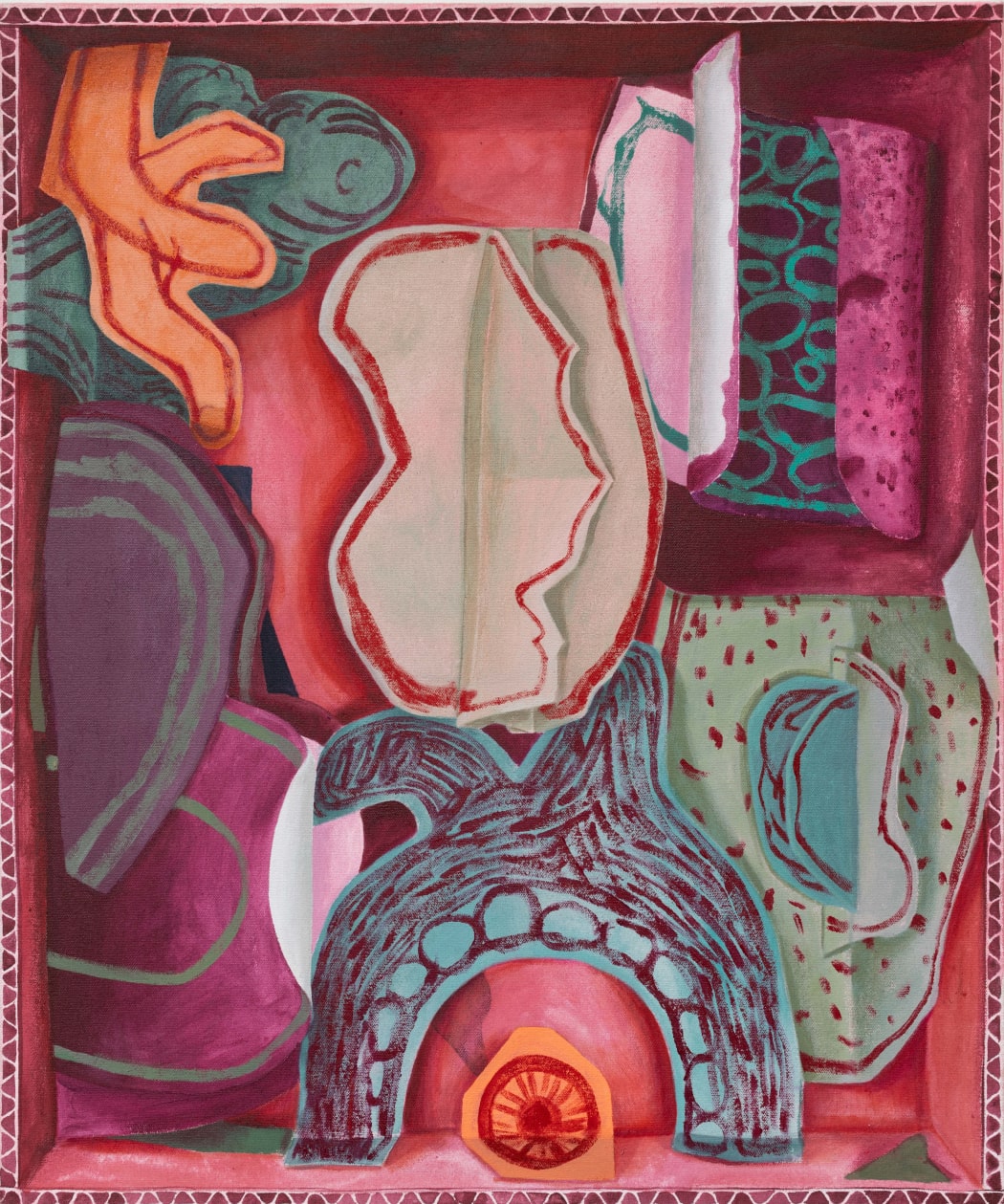

Dismember My Monster

Accompanying text by Bryan FultonLottie Stoddart’s second solo exhibition with THE TAGLI presents Dismember My Monster. -

Lucas Dupuy, Waiting For

Lucas Dupuy, Waiting ForNew Geographies

Accompanying essay to the exhibition by Hector CampbellWell-trodden tracks, reimagined routes and peripheral pathways map THE TAGLI's latest group exhibition 'New Geographies', presenting wide-ranging responses to actual and emotional landscapes. Considering how we at once navigate, interpret and construct our own surroundings, the assembled artists touch on psychogeographic examinations of self identity, the ever-changing topography of memory and architectural adaptations within public and private space.

Artists such as Thomas Cameron and Nassim L'Ghoul turn directly to their environment as a source for subject matter, offering timely reflections on the lived-experience of existing within a twenty-first century city. Cameron's solitary figures inhabit immediately recognisable urban settings, complete with contemporary street furniture, shop windows and service counters. Just as his paintings serve to expose the unexpected anonymity and loss of individual identity that comes from acclimatising into a metropolitan society, L'Ghoul's cast metal miniatures focus their attention on the debris and detritus that these collective consumers discard. The littered surfaces of certain German streets are rendered in hyper-real, almost religious, reliefs that elevate the overlooked, ground-level remnants of everyday life.

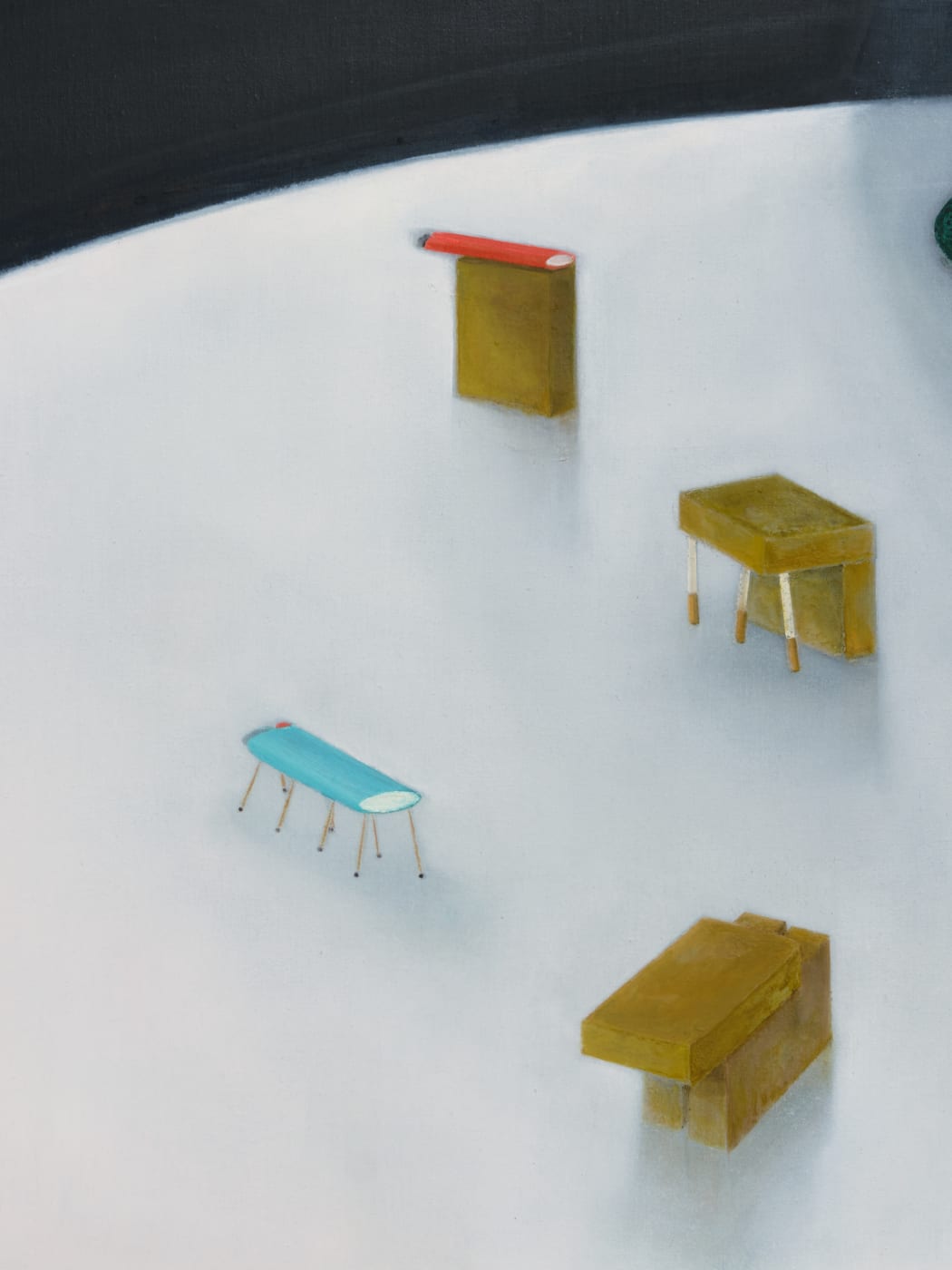

Similarly drawing from pre-existing, societal sources, Afonso Rocha presents a skewed, subverted exploration of those inter-personal relationships that play out in public. Figures are transplanted into an idealised, caricatured exterior of lush green lawns, bright blue skies and perfectly-plump white clouds - against which they perform scenes of imagined intimacy, as if inhabiting a testing ground for awkward experimentation. Such world-building, the act of inventing an exterior world that more accurately reflects one's interior concerns, ideas and identity, is also evidenced in the practices of Tom Woolner and Piers Alsop. Constructed by the layered piping of pigmented acrylic resin, Woolner's archeological panels present as part-painting, part-fresco, part-fossil. Pastoral, corporeal compositions rendered in a pastel palette appear intestinal as the fluid medium banished any and all hard-edged angles in favour of a landscape of soft corners and smooth curves. The characteristic warp and weft of Alsop's jute canvases, meanwhile, serve as the theatrical backdrop to staged sets that sit as if awaiting activation. Embracing abstraction, ambiguity and yet potent with potential, each sentimental vignette is imbued with the awareness of an imminent, implied narrative.

Elsewhere, works by Leon Scott-Engel and Toni de Jesus offer material responses to their immediate environs. The former's hand-made, curved canvases adhere to the pre-existing architecture of the space, and have been known to tuck themselves into or curve around corners, on occasion even slumping anthropomorphic onto the floor below. Scott-Engel's painted panels too appear acutely aware of their own medium, with his intimate, cropped compositions at once interrupting and embracing the wood grain. Toni de Jesus' terracotta and porcelain sculptures, however, act as if in opposition to their physicality. Vessels precariously held-up by spindly, supporting protrusions highlight both their inherent fragility and the more conceptual instability the artist feels working at the much-debated intersection between craft and fine art.

Finally, Lucas Dupuy and Harm Gerdes demonstrate abstraction's ability to interrogate and elucidate our relationship to space. Mark-making primarily with airbrushed acrylic, both artists present shapes and forms seemingly unconfined to the borders of any particular picture plane. Such implications of an unseen yet continued existence demonstrates an empathic observation of their surroundings and what it means to move into, out of and through an as-yet-unmapped terrain.

-

“ Water flows, but it also lingers...”

A conversation between THE TAGLI founder and director Dimitrios Tsivrikos and artist Heeyoung Noh on her solo exhibition, Submerged Attachment, presented by the gallery at 67 Great Titchfield St, London.

-

In Conversation: Christian Bense and Dimitrios Tsivrikos, Blending Art and Design

London Design Week 2025Our founder Dimitrios Tsivrikos sat down with renowned interior designer Christian Bense for an insightful discussion on blending art and interior design. This conversation was a part of The London Design Week 2025 Access All Areas Programme, taking place Tuesday 11th March.

DT: Christian, could you start by sharing the core philosophy that guides your work as an interior designer?

CB: We have a saying in the studio: “Establish first what is right for the home, then what is right for the client, and then establish a style that works for both.”

At its core, this implies an objective approach to the way we design—ensuring that we have thought about more than just the immediate wants and "nice-to-haves," and focusing instead on finding the right solution regardless of style.

The “style” element of a design can easily be incorporated once you have an ironclad solution to what is right for the home.

DT: Your designs have a wonderful balance of timelessness and character. What’s your approach to ensuring a space feels lived-in yet refined?

Our ideal project is a “forever home.” To me, a forever home is one that stands the test of time—feeling as though it has been designed over a period of years rather than being trend-led or confined to a single era.

A forever home features layers of materials and textures; it doesn’t try to be "matchy-matchy." When you apply these principles to a design, you can still create a lived-in home—one with life and character—without sacrificing a tailored and refined feel. Art plays an enormous role in this for us, as I truly see artwork as transformative to a space and the ultimate finishing touch.

DT: For someone (either a homeowner or an interior designer) looking to incorporate art into their projects, where should they start?

CB: I’m not one for throwaway advice when it comes to interior design, so I really dislike it when people say, “Just have fun with it” or “Follow your gut.” But when it comes to art, I often find that people struggle because they overthink it.

There are designers who will tell you to “start with art,” but I feel this creates a barrier to entry—implying that you need to love a piece enough to design an entire room around it. I see art as an accessory to a room—a finishing touch that adds variety and interest—not the starting point of a scheme.

So, in this case, I would say: don’t overthink it when it comes to art. The room and the art do not need to match. Choose pieces you absolutely love—this will make the beginning of your “art journey” much easier to embark on.

DT: Commissioning artists can be a game-changer for a space. How do you approach selecting the right artist for a project, and why is it important?

CB: I’ll be honest—I’m 50/50 when it comes to commissioning pieces. When we’ve done this for clients, it’s usually because we need something highly specific in terms of scale or subject matter, and a commission is the best way to achieve that.

When we do commission pieces, it’s often because a client has a favorite artist, and commissioning a piece is a perfect way to create something unique to them. I would always keep that in mind—if you’re commissioning something, make sure it’s personal to you.

Where commissions can sometimes be a letdown is when you start defining too many parameters for the artist, which can, at times, stifle their creativity. It’s rare, but it’s important to ensure that meeting your brief doesn’t go beyond what the artist naturally does best.

You should always be inspired by an artist’s work in general and avoid commissioning a piece simply to replicate a client’s previous work or copy another. A commission is an opportunity to own something one-of-a-kind, but it’s equally important to honor the artist’s creative process.

It’s important to have an idea of where art will go in a room and what you want it to achieve. For example, should it act as a focal point, or does it need to help... with the proportions of a room. Does it need to add some colour some softness etc. Going back to my comment about establishing what is right for the room will help you provide parameters to your selection process, which is often needed when the options and endless.

DT: Mixing contemporary and antique pieces can be tricky. Do you have any rules or tricks for making them work together seamlessly?

CB: I’m quite relaxed when it comes to mixing styles because I like art to feel as though it’s been added over time. In that regard, I focus more on the composition of the artwork on the wall or within the room. However, for clients who prefer more structure and order, we spend a lot of time and energy on how pieces are framed.

If you maintain a common thread in how you frame pieces—particularly those hung as a group or series—you can mix periods and mediums to your heart’s content while still creating a sense of cohesion.

That doesn’t mean all frames should match, but reframing pieces with intention allows you to adapt elements of the artwork to better connect with the overall scheme or other pieces of art.

DT: Lighting can transform how art is perceived in a space. What are your top lighting tips to make artworks shine?

CB: If you are in a position to adapt lighting to suit the space, it’s crucial to plan where your art will go so you can tailor the lighting accordingly.

When it comes to lighting art, one size doesn’t fit all. If you have a wall or space where you know there will always be a large piece, this is an opportunity to make lighting that artwork a feature—you might consider picture lights or ceiling spotlights. While the artwork may change over the years, planning for it ensures the room is adaptable.

Plug-in wall lights are a great solution when you’re perhaps not in a position to finalise the exact location of your fitted lighting. We often include adjustable lights in our schemes, allowing you to tilt the head to direct light toward or away from the artwork as needed.

Not to beat a dead horse—but if you’re undertaking a renovation and know that artwork will play a role in the design, plan ahead. Think about what is right for the room first, and you’ll have all the options available to you when selecting artwork later.

DT: What’s your take on ‘statement pieces’—should every space have one, or is subtle layering more effective?

In my home, I have a mix of both in the same room—partly out of necessity, as I have quite a lot of art. I mentioned this earlier, but I think it’s important to ask what the artwork needs to achieve in a space.

Is it a large photograph that adds depth to a room or a space with a less-than-ideal view? Is it a series of smaller pieces that invite you to step closer and engage with otherwise empty areas? Or are they bold, large-scale works that make a statement and are visible from multiple vantage points?

Think about what is right for the room—what the room needs—and then find a piece that fulfills that purpose.

DT: What role does storytelling play in how you select and place art in an interior?

CB: There are two ways you can look at this. Do you have a story to tell about each piece of art? Ideally, yes. It might sound pretentious but having some sort of story to tell and a personal connection to a piece is really great, as it encourages you to think beyond whether the piece will fit into a room or not.

The other way art impacts storytelling ties back to the idea that art is an accessory. Just like in fashion or even baking, the right accessory can help drive the story home. If you want a space to feel chic and sophisticated, maybe photography or etchings will help. Likewise, if you want a space to feel more grown-up or formal, oil paintings in ornate frames can help. Regardless of the room’s style, I believe the selection of artwork can provide that point of difference between spaces.

DT: What’s one piece of advice you’d give to someone hesitant to take risks with art in their home?

CB: Quite simply, only buy pieces you love. That way, you’re not taking a risk on the artwork—only on where you hang it.

DT: When incorporating art into interiors, what’s the biggest mistake people make, and how can they avoid it?CB: For me, it’s one of two things: being monotonous or being confused. Only buying the same type of art will make for a boring home and stifle the storytelling element, but equally, not being able to edit can make spaces feel confused.

Zone off your art styles so each piece can shine, rather than cramming them all into one space. Also, ensure the artworks are allowed to shine by not crowding them with pieces of another style.

Buying art isn’t just about filling your walls with anything. Make sure you don’t diminish the impact of the art by taking an “anything goes” approach to how or where it is hung.

-

View of the Whitechapel Gallery's exhibition, 'Gavin Jantijes: To Be Free! A Retrospective 1970 - 2023’

View of the Whitechapel Gallery's exhibition, 'Gavin Jantijes: To Be Free! A Retrospective 1970 - 2023’ -

-

-

TELL ME EVERYTHING YOU SAW AND WHAT YOU THINK IT MEANS

Essay by Yates Norton, curator of 'Tell me everything you saw and what you think it means'. The exhibition features Piers Alsop and Grant Foster.Looking at Piers Alsop’s and Grant Foster’s work is like reading the descriptive passages in a story. In description, the forward motion of narrative is suspended; we linger on details, drawn as much to the luminous quality of something as to its dark and unknowable other side. We might understand this descriptive mode that characterises the artists’ work as a kind of ‘looking with’ rather than ‘at’ the world. It is a way of looking that doesn’t seek to marshal disparate elements into a linear narrative or consistent meaning, but one driven by curiosity and shaped by a humility of seeing the world as something to draw close to while knowing it is always something that we can never fully know or indeed comprehensively describe. One senses in their work a desire to be close by, and return again and again to, a scene, object or memory. This is what gives their work a peculiar quality of intimacy.But this intimacy isn’t all warmth and ease. It is shaded by a sense of unfamiliarity. The experience is like contemplating an ancient artefact or tale: we recognise some things, like love, pain and the apparently unchangeable habits of eating and drinking from a story told 2,000 years ago, and yet these worlds remain ungraspably strange. In the artists’ work, it is as if we encounter a visual language that is just out of reach where something has been lost in translation over time. We see, for example, in Alsop’s Civil Twighlight (2024), how he describes familiar things as if articulated with some foreign tongue. Look at the flower: it appears somehow desperately yellow and frantically optimistic, startled by its own appearance against the shadowy background and the ominous outline of a thumbs up. Or we may see in Foster’s paintings of little animals and the back of a child’s head, (Mouse, Child, Lust, all 2024), a particular quality of line that seems reminiscent of another age; 1950s England perhaps, one that longed for innocence and games on hot summer days, but which was also haunted by unease and dissatisfaction. Looking at Alsop’s and Foster’s works is like listening to a tune we thought we knew only we hear it limned by faint harmonics and some strange and distant roar.In Middlemarch, George Elliot observed that we too often armour ourselves against the intensity of the world around us. ‘The quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity’, she writes. She suggests that we do so because were we to fully submit to the world in all its profound mystery we may not be able to bear it: ‘If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heartbeat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.’[1] When Alsop notes that he tries to reach for a sense of ‘loud silences’ in his works, perhaps he, like Elliot, is trying to offer the viewer at least just a glimpse of this unbearable mystery in the familiar.[2] Seeking to introduce ‘weight and ambiguity’ in his works, he creates a mood that is ‘like obelisks that seem significant and pregnant with meaning, but we don’t know exactly what that is.’ Foster also reaches for ‘Ambiguity (but not meaninglessness)’, attempting to give the viewer the space to not know, to find not non-sense, but no one sense. For both artists this ambiguity is at the heart of making the work, where rather than corralling painting into preconceived form, they follow it ending up with ‘something I have never imagined as a result of trying to preserve some part of it’ (Alsop). The ambiguity is also part of viewing the work, where we enter into an ‘interlinking chain of questions’ (Foster) rather than being offered coherent answers and fixed symbols.This ambiguous atmosphere is found in even what is most familiar to the artists. Apparently simple memories and images are shadowed by some darker, stranger undercurrent. Family members, children’s illustrations, memories of a particular place are not remembered and pictured with bright lucidity but coloured with both humour and melancholy, as if at the heart of what is remembered there is at once the joy of its remembrance and the pain of its loss, a spectre of longing that haunts what might seem innocent or known. See for example Will’s retrospective at the breakfast table (2024), a deliberately bombastic title which pictures Alsop’s memory of his father, the famed architect Will Alsop, ‘sitting in his white shirt at the table in the flat I grew up in. He always sat in the same place.’ The little maquettes are miniature versions of his father’s buildings made from cigarette packets and lighters. As Alsop explains: ‘being a committed smoker, the running joke in my family was that all his designs were derived from differing arrangements of B&H packets and Bic lighters.’ This army of buildings forms a delicate defence system around the boiled egg and toast, like a kind of medieval village stranded on a linen moon. Affectionate and humorous, the painting both celebrates his father’s work and, as Alsop notes, ‘playfully minimis[es] his/and more broadly the notion of achievements.’ It is a work that reaches back to the tradition of the still life and memento mori, a reminder of the banality of creaturely habit and the inevitable passing of life and work.Grant too draws on fragments of memories of home and family. In Panspermia (2024) the two figures are based on a photograph from the 1960s of his mother and uncle as children dressed in their Sunday clothes. The large sweeps of white make it seem like we are looking at an image in the process of whiting out into nothing, while the spiral-eyed creature on the back of the painting gives the whole work a sense of some weird trip, where the starched whiteness of proper 1960s Englishness is warped into some frightening vision on the cusp of disappearing. The colour white is not without certain racialised freighting. Afterall, both Grant’s mother and uncle had come to the UK from Trinidad and the artist recalls the complex relationship to all the dominant signifiers of England and Empire –– Enid Blyton, country walks, feeding swans in the park–– that his mother and uncle faced and negotiated. But as ever in Grant’s work, no one form, colour or reference predominates over the other, they are all mixed up and animated together, as if we were flicking back and forth the pages of a scrap book. It is a visual reminder that power or indeed meaning can never be totalising; they can be dismembered and remembered into fractals of other senses and meanings.These shifting moods and colours give their work an atmospheric quality, where atmosphere has the paradoxical quality of being both palpably visceral and oddly elusive, associational and mysterious. For example, in Alsop’s Memory Loss (2024), a cloaked figure stands or hides awkwardly behind a lamppost set against a furious and sulphurous sky that seems to congeal, bringing this distant space right into the foreground with its thick painterly texture. Alsop’s work reminds us that atmosphere is not simply a static backdrop against which human activities unfold but is a dynamic force that we are deeply embedded within. This sense of space and atmosphere is evoked, albeit claustrophobically, in Hunky Dory, where Alsop paints the mottled bluish, greenish white of what is a reference to a plaster wall (perhaps thick with damp and moulding organic life) with black marks that are based on the fake beams of a mock Tudor house. It is a work that is at once a vision of sodden, suburban England and one that is surprising like a piece of canonical abstraction. In another work, Ghost (2023), he paints a no-nonsense bench of the kind a local authority would design against a landscape that is lit up as if by the headlights of a car, turning it into a swarm of colours, eerie and close, like the wallpaper in a Vuillard painting of an interior. For Foster too, painting has the capacity to play with the ambiguity of atmosphere. In Then to Now (2012), he uses watercolour, a medium as aqueous as the faint memory it traces of two figures –– himself and his mother –– to suggest they are either emerging or disappearing into the white of the paper. And in the painting Circular Time (2024), we find a figure almost materialising or dematerialising, an amorphous body latent with either power or pathetic vulnerability. Atmospheric as a cloud, this creature is apparently suspended between boldness and inebriation, its enormous hand and dynamic swagger suggestive of either spectre or giant.Ambiguity involves this state of suspension between states. Suspension can be understood not so much as a pause as a stretching, as the word’s etymology implies. It disrupts a linear approach to time in the same way that passages of description do not so much drive narrative forward as draw it out, compelling readers to reflect on the quality of the text as much as its plot and meaning. As the philosopher Lars Spuyboeck puts it, suspension is a state of ambiguity and indeterminacy, the ‘jump that has not yet landed.’[3]It is no surprise then that the artists chose to title their exhibition with a line from the film Rear Window, directed by one of the great masters of suspension Alfred Hitchcock: ‘Tell me everything you saw and what you think it means’. Just before Grace Kelly delivers this line, she says, ‘Let us start from the beginning again’, told with a frisson of pleasure, as if the process of looking and describing is one that can never be done with, that the very suspense of not-knowing and not-seeing everything is one which she–– and we as audiences –- want to experience again and again, with no resolution and no end. Afterall, if all is said and done, what more is there to see? -

Collaboration with The List - House & Garden

Featured Designer 2024We are delighted to be featured as one of The List - House & Garden's Feature Designers of 2024.The List facilitates the search for inspiring design for homes and gardens around the world. They provide a directory of design professionals, located across major cities around the world, to connect clients to their dream decor objects, whatever their inspiration my be.By featuring on The List, we are tremendously excited to be able to bring our expertise and knowledge to their clientele. Art has the potential to transform visions, elevate sensations, and imbue an environment with an incredible balance.At THE TAGLI, we offer curatorial expertise and consultation services to both novice and seasoned collectors. Being active in both primary and secondary markets allows us to provide a wide range of cutting-edge options to interior design projects. Through our teams’ many years of experience working closely with architects, interior design studios and developers, we have provided artworks to a plethora of different types of settings, aesthetics, budgets, and requirements. We are distinguished by our attention to detail which allows for us to make any space feel both inviting and refined through the artwork we provide. We value careful conversations with our clients in order to best deliver their vision. From here, we enjoy the creative process of finding incredible artworks to fulfil their bespoke needs. Through our extensive networks, we handle all logistics, framing preferences, and installation needs. The final product is tremendously exciting as the initial conversation with our client becomes transformed into a beautiful reality.The List is an exceptional directory. We are honoured to be included among their London-based designers, and we look forward to a fruitful collaboration.To find out more about our advisory services please click here. -

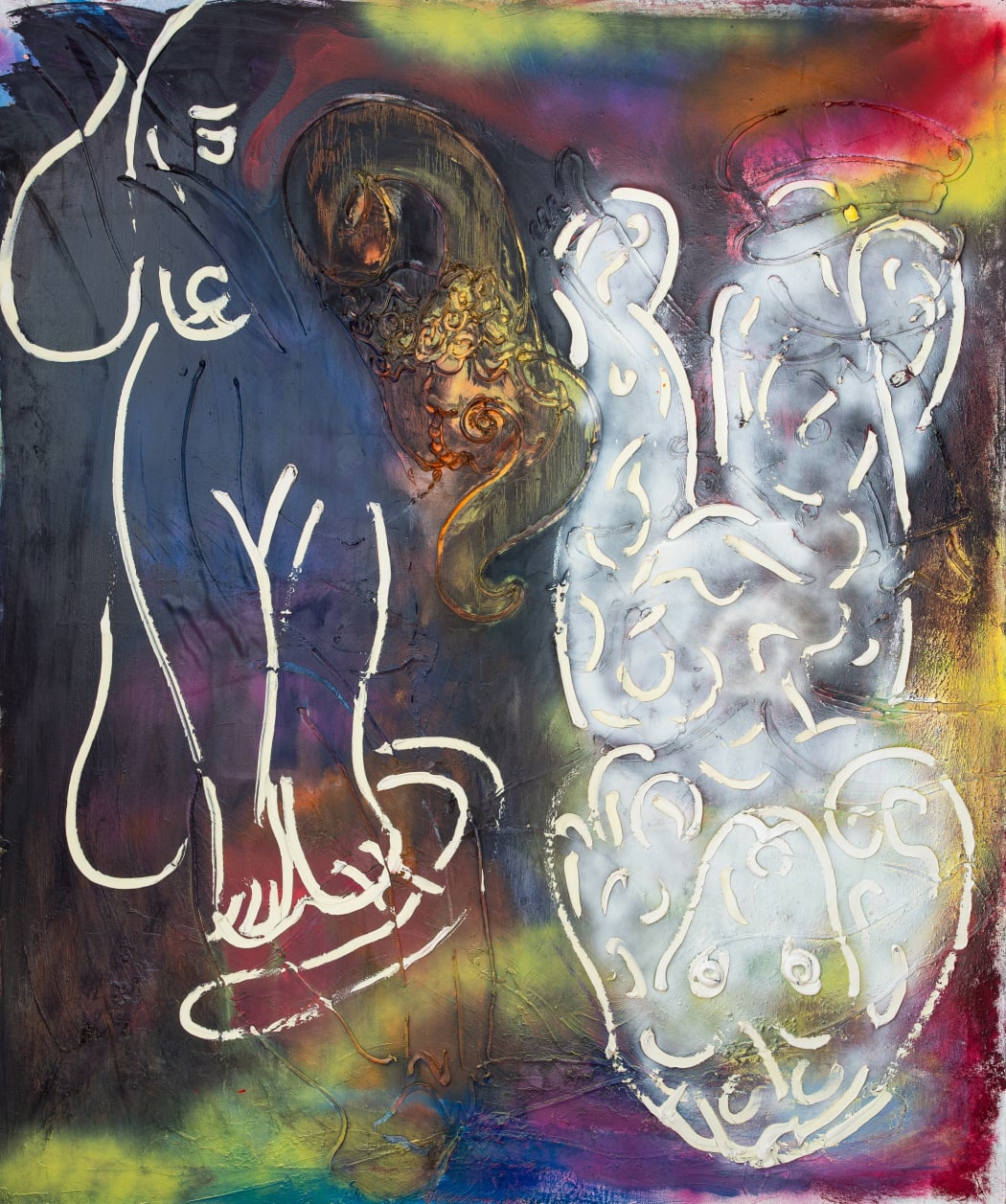

Grant Foster, Mephistopheles (Front), 2020THE TAGLI posed a series of questions to artist Grant Foster, seeking a deeper insight into his artmaking process. Working across painting, sculpture, collage, and text, Grant uses irreverence as a tool to readdress the dogmatic traditions of the past and the present infallibility of reason.

Grant Foster, Mephistopheles (Front), 2020THE TAGLI posed a series of questions to artist Grant Foster, seeking a deeper insight into his artmaking process. Working across painting, sculpture, collage, and text, Grant uses irreverence as a tool to readdress the dogmatic traditions of the past and the present infallibility of reason. -

The Tagli Team recently visited Caroline Ashley in her studio in London. She shared insights into her process of making, the importance of materiality and discussed her defintions of action based performativity.

Ashley's practice explores assemblage, soft sculpture; referencing repetition and hand driven processes. Her tactile works invite the viewer to fragment their reflection and engage in spatial play.

-

The Tagli Team recently visited Hugo Lami in his studio in London , where he spoke to us about what inspires him, his process of painting and the symbolism in his work.

Hugo Lami is a Portuguese artist living and working in London. Lami's work addresses our social dependence and identity crisis caused by the absurdity of the digital and the virtual world. His work depicts dreams of alien landscapes and organisms in constant interaction and evolution trying do define their identity.

-

THE TAGLI Founder Dimitrios Tsivrikos sat down with Gasworks and Triangle Network Director, Alessio Antoniolli to discuss the organisations mission, residency program and the pivotal role of community and transparency in achieving success.

This enlightening dialogue is a valuable resource for artists and individuals aspiring to engage with the vibrant London and international contemporary art landscape.

-

The Tagli Team recently travelled to Cambridge to visit Lottie Stoddart in her studio, where she spoke to us about her process of making, what inspires her and what she enjoys about people encountering her work.